Besides its imaginative functions, political poetry plays another essential role usually considered the antithesis of imagination: documentation. The narrative we’ve been fed since childhood has been shaped by the patriotic whitewashing of textbooks and the hometown cheerleading of the media. Yet we are accustomed to the luxury of dissent, and in recent years alternative re-tellings of the conventional American backstory have gained a foothold – military bases re-named, statues pulled down, Black and Native American and Women’s Studies taught in universities.

But now it’s our turn to confront one of the unmistakable watermarks of authoritarian rule, as foreseen by the Prophet Orwell: the “official story,” with its enforced forgetfulness of troublesome facts. The Trump regime is determined to expunge from living memory the terrorism of slavery and the Klan, the hard-won sovereignty of women over their own bodies, the rich panorama of sexual identity. With shocking suddenness the newsreel of history jerks into reverse, erasing a century of popular struggle for civil rights, women’s rights, gay and trans rights, even the clear consensus of climate scientists and medical researchers.

Yet the facts bulldozed under by what the victors call “history” cannot be lost if the testimony of witnesses can be preserved. The political poet bears witness to the victims of the victors, their lives and deaths and unexplained disappearances, and to those who march in their names to re-affirm the promises of democracy. Not in their millions, as a journalist or historian would, but face by face, voice by voice.

As a young poet, Carolyn Forché traveled to El Salvador in the late 1970s to work as a human rights advocate. After she returned she published The Country Between Us (1981), a book of poetry deeply scarred by her immersion in that country’s bitter civil war, along with an essay in which she declared, “It is my feeling that the twentieth-century human condition demands a poetry of witness.” The poetic power of her testimony re-ignited in the Reagan era a controversy that had been simmering since the 1960s over the role of politics in poetry, and vice versa.

“Something happened along the way to the introspective poet I had been,” Forché recalls in the Introduction to her anthology Against Forgetting. “My new work seemed controversial to my American contemporaries, who argued against its ‘subject matter,’ or against the right of a North American to contemplate such issues in her work, or against any mixing of what they saw as the mutually exclusive realms of the personal and the political.”

The phrase “poetry of witness” soon took on a life of its own – “regarded skeptically by some,” Forché later wrote, “as a euphemism for ‘political poetry,’ or as political poetry by other means.” But as defined by Forché, it means poetry that inseparably fuses the personal and the political in the crucible of the poet’s own experience of what she calls “extremity”: war, imprisonment, enslavement, torture, exile, imminent execution.

A Literary Myopia

Participation in the political realm is only one dimension of living a full life. Yet without it, a twenty-first century human life is incomplete, like a body operating on only six of the seven chakras recognized by traditional Asian medicine. We are social beings, and any human society requires some form of governance. If we don’t participate, we yield the right of self-governance to those who would govern us.

Like everyone else, poets have private joys and concerns: a personal history, a love life, family life, spiritual life, a relationship with nature, a connection with place and an urge to travel. But we also have a place in society, an ethical responsibility to our communities, a role in the economy that feeds us. Each person naturally values some of these aspects of life over others. But a large segment of the U.S. population has opted out of the political sphere entirely, disavowing even the right to vote.

Given the corruption, rancor, cynicism and deceit on constant display in the news, that is understandable. But in my opinion it is precisely this abdication of responsibility that has led to the atrophy of our democratic order, and it can only get worse. As Thomas Mann wrote in a letter to Hermann Hesse, a fellow refugee from Nazism, in 1945: “I believe that nothing living can avoid the political today. The refusal is also politics; one thereby advances the politics of the evil cause.”

Like the non-voters among us, poets who shun the political domain of life are turning their backs on an essential piece of their humanity, and on millions of their fellow humans who are denied the luxury of making that choice. As the Trump regime pushes ahead with its authoritarian agenda, I think we will all find the political realm rudely intruding into what we once considered our private lives.

“If we give up the dimension of the personal,” Carolyn Forché writes in Against Forgetting, “we risk relinquishing one of the most powerful sites of resistance. The celebration of the personal, however, can indicate a myopia, an inability to see how larger structures of the economy and the state circumscribe, if not determine, the fragile realm of individuality.”

In Duncan Wu’s Introduction to Poetry of Witness (2014), a companion anthology he co-edited with Forché, he echoes her metaphor of myopia, a tunnel-vision “peculiar to recent times,” and adds, “Prior to that, poets commonly discussed experiences shared by the larger community in which they lived.”

We owe much of our culture’s literary myopia to the way American military might has shielded middle-class America from the horrors of tyranny and war, even as our taxes financed those selfsame horrors in places like El Salvador and Palestine. The exceptions to “American exceptionalism” can be found in poetry by people of color, immigrants, prisoners, activists, and others often excluded from the Bill of Rights, and until recently from the literary canon as well.

Poetry as Evidence

Against Forgetting (1993) contains over 700 pages of work by 20th-century poets that carries the weight of “extremity,” most of it translated from other languages. Poetry of Witness (2014) collects another 600 pages of poetry written in English under similar conditions, reaching back five centuries. Both books offer only a fraction of the material their editors unearthed. This vast body of poetic work demonstrates that “poetry of witness” is a universal response to political adversity. It’s not just “political poetry,” Forché contends, or even just poetry, but evidence, documenting what we humans are capable of doing to one another, and what we are capable of surviving . . . if we survive.

The term “witness” thus likens the poet of extremity to the witness in a court of law. But to me, it also evokes the Christian evangelical practice of “witnessing” to the unsaved. Though neither Wu nor Forché mentions this connotation, Wu hints at it when he quotes Forché’s assertion that “poetic language attempts a coming-to-terms with evil and its embodiments, and there are appeals for a shared sense of humanity and collective resistance.”

Poetry of witness expresses a fundamental faith that connection through language ultimately matters, even when the poem is discovered in a pocket of the poet’s corpse. This, Wu believes, “has always been the means by which the imagination has articulated its response to war, imprisonment, oppression, and enslavement.” Poetry, he argues, with its capacity to express “the sublime, the ineffable, that of which we cannot speak,” offers the language “best suited to the task.”

Lest we forget, the war Forché brought home to us was never just a Salvadoran war; we ourselves were funding the right-wing dictatorship whose atrocities she documents. Some of the poems collected in my new book Honk If You’re Awake! date back to that era, a time of mass protest against apartheid and the Bomb as well as Reagan’s Central American wars. You’ll find references to the Civil Rights movement, which I barely remember, and the Vietnam War, which ended just as I reached draft age. Unfortunately, none of these issues has truly receded into the past, and in the Trump era they are rebounding with a vengeance.

Under George W. Bush we found new Vietnams in the Middle East to bomb, invade, and occupy. Under Obama, a C.I.A.-orchestrated coup toppled a democratically elected government in Honduras. Under Biden, my taxes continued to arm and finance a heartless apartheid regime in Israel and a merciless campaign of vengeance far surpassing the Old Testament dictum of “an eye for an eye.” Under Trump, on the threadbare pretext of a “War on Drugs,” U.S. Navy warships are sinking Venezuelan fishing boats. And the threat of nuclear war, though it has faded into the background of our daily political melodrama, hasn’t loomed so dangerously high since the Cold War.

Meanwhile, the true greatness of America is under assault: the idealistic impulse that defied privilege and power to emancipate the slaves, extend the vote to women, grant workers the right to a decent life, provide for the sick, the elderly, the poor. A meaner, greedier America now proclaims that what makes this nation great is not democracy but empire – the ruthless invasion and plunder of a continent, the dehumanization of dark skin and the technology of superior force.

All of this is breaking news – but it’s nothing new. The poetic imagination bears witness to what is happening down here on the ground, but it also soars high above, tracking the repeating patterns of history.

Next month, Part 3: Democracy & Empire

Note: These are my personal opinions and do not represent any organization I’m involved in. If my words resonate for you, please share widely. You can subscribe (or unsubscribe) at StephenWing.com. Read previous installments of “Wingtips” here.

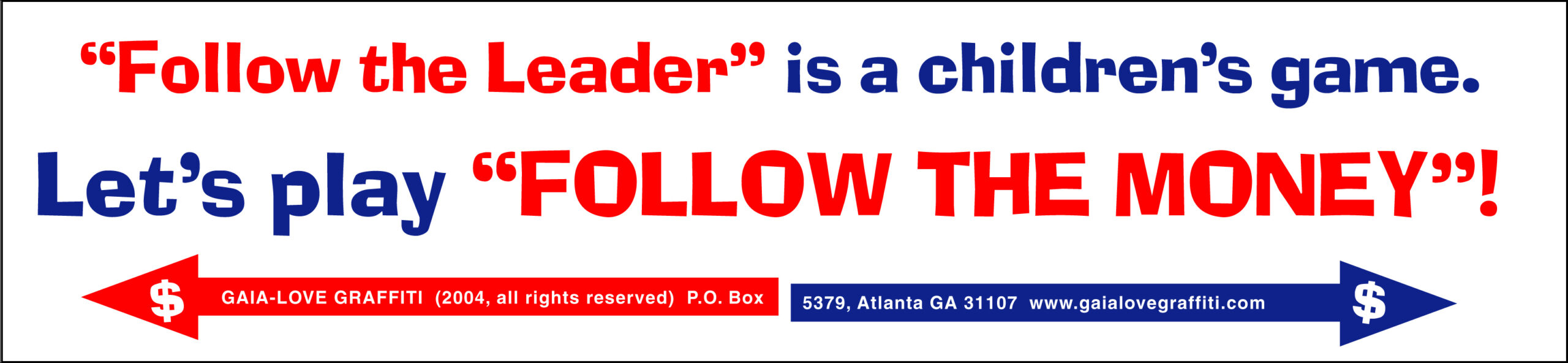

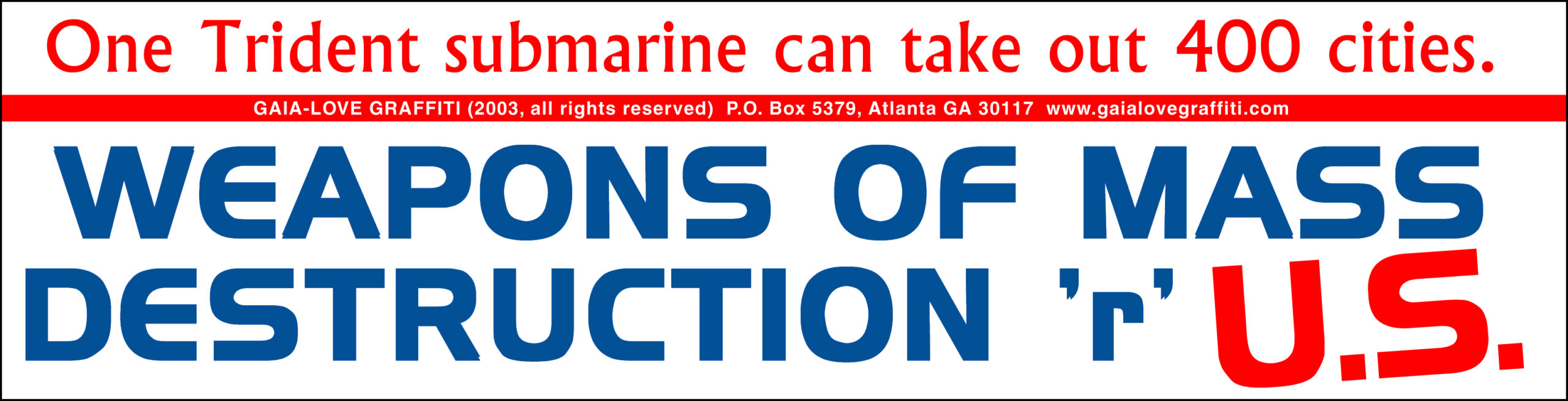

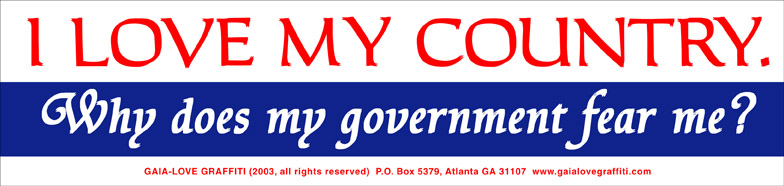

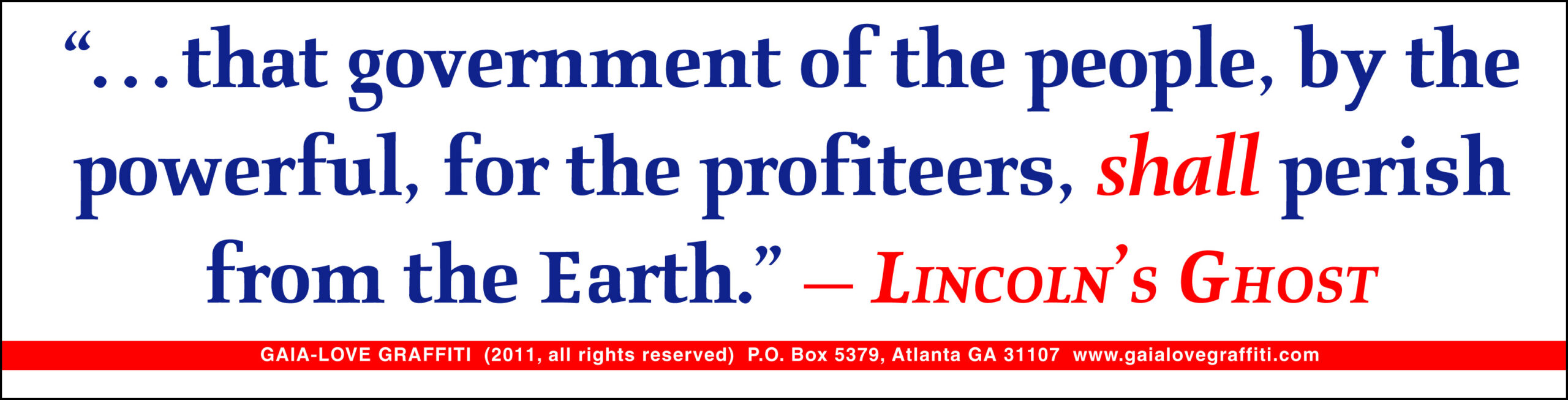

Wing’s original

stickers available at

GaiaLoveGraffiti.com

0 Comments